Recently, I was re-reading the book ‘luxury brand management’ wherein the authors – Chevalier and Mazzalovo – suggest three criteria to classify a luxury item: (a) strong artistic content; (b) unique craftsmanship and (c) international reputation.

While I agree that the artistic content and craftsmanship is what differentiates most luxury product and brands from non-luxury, I somehow struggled with the idea of ‘internationalization’. The authors argue using an interesting point that a significant part of luxury brand’s business relies on consumers who are far from home country. This means that the other consumers in different markets must also realise the brand to be a luxury. This classification point of

internationalization misses on two fronts I guess. One, it creates the problem of massification (I have dealt with this issue in two of my earlier posts ‘Massification of Luxury: the Chinese Invasion’ and ‘If most people can have it, is it Luxury’. Secondly, it omits completely the local dimension of luxury. In this post, I wish to focus on the ‘local dimension of luxury’.

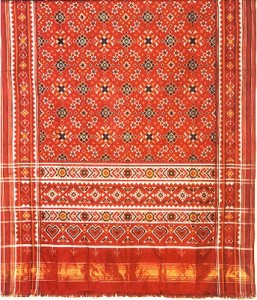

To put simply, I define ‘local luxury’ as a luxury product and/or brand which is not internationalised at all however, has a significantly strong association with luxury in its local (regional) catchment area. Examples of such luxuries can be found throughout the world wherein generations of craftsman have been producing luxury. One striking example is such in an emerging market like India would be the Patola (a kind of a sari wore by woman across the Indian sub-continent) from Patan (http://www.patanpatola.com/).

Among Gujaratis (i.e. people from the state of Gujarat in the Western Zone of India with a population of approximately 50 million or more) patola is something legendary. The popularity of it in the luxury local circles is such that the order book has got a seriously lengthy weighting list. The amazing quality of the Bandhani (the finished textile product) has its origins in a very complex and tricky technique of ‘tie dyeing’ or ‘knot dyeing’ known as “Bandhani Process” on the warp & weft separately before weaving. There is only one family in the city of Patan (in the North Gujarat) which has been producing this quality product for the last ‘seven centuries’.

It is hardly international but it’s clearly a luxury. Every patola is unique in its design (none two are similar) and to do that for 700 years itself is mind-blowing. Moreover, the artistic content and unique craftsmanship is remarkable. A patola costs probably 100 times or more in comparison to a normal sari.

Similarly, the chocolaterie in Brighton, UK called Choccywoccydoodah (http://www.choccywoccydoodah.com/) for the last 3 generations, has been producing amazingly creative chocolate one-off sculptured fantasies, bespoke wedding cakes and other items from chocolate. While it being a food item, one can imagine it will have a strong local dimension but there is nothing stopping it from becoming ‘international’. Paul from France has been international for quite long while.

I believe, the generic criteria of internationalization in this sense would hardly be able to capture such amazingly beautiful and exceptional artistry and craftsmanship. I am sure such unique examples would be present across the world wherein the luxury brand has got such a strong local dimension and hardly any international presence.

The major point I wish to make here is that in continuously focusing on the ‘international brands’ in our luxury debate, we are mostly missing out on some other substantial dimensions of luxury.

I would really like to learn from you all readers about your own experiences of such unique luxury brands which are hardly international but have got a very strong local dimension. Please share.